Note: To read earlier chapters click on the desired title in the “Chapters” listed in the sidebar on the right or at the bottom of the page.

“Mrs. Lena Zimmerman Willems was born in South Russia in the Firstenland in Syejowka on February 6, 1893, to Rev. and Mrs. H. H. Zimmerman, and departed this life at the age of 70 years, 5 months and 24 days in a Tulare, California hospital. She came to Winkler, Manitoba, Canada, with her parents in 1903. In 1906, she moved with her parents to Waldheim, Saskatchewan.” Lena Willems Mimeographed Obituary 1963 My Grandmother Willems was born in Russia and spent the first ten years of her life there. I learned that when I was a little girl. Yet even though I loved hearing stories about “the olden days,” I never thought to ask about her childhood or the long trip that took her and her family to North America. When I was around her I simply enjoyed her concrete presence. She was occupied with her own thoughts, and I was occupied with mine. She lived in her adult world; I lived in my child-world, a mental barrier we both respected. Grandma was born in Russia, but the language she spoke with her husband and children was Plautdietsch, a Low German dialect. The language spoken at the service she attended at the Dinuba Mennonite Brethren church was High German, the Bible she read each day a German Bible. People who moved from one country to another took their native language with them—my parents were both been born in Canada, yet their first language was German, not English. It didn’t seem at all strange that my Russian-born grandmother was not actually Russian. My question was not whether the Willems family was Russian or German; it was whether we were German or Dutch. When I was a little girl during WWII, Dad said we were Dutch. I liked that idea, imagined myself as a little Dutch girl wearing wooden shoes, a long full skirt with a tight bodice and a white cap with wings on the side. That didn’t square, however, with the fact that Grandma and Grandpa spoke German, not Dutch. When I asked my mom about this, she said that we were really German and that the reason my dad said the Willems family was Dutch was because of the war. The Germans were Nazis, the enemy. Dad did not want to be identified with them. It must have been well after the war when Mom told me this, probably after Dad began to refer to himself as German during the 1950’s when Germany began to be rehabilitated in the public image. I reluctantly gave up my Dutch-girl fantasies and began to see myself as German. This sense of being “German” stayed with me into my early 20’s when I happened to read a book about Mennonite history. I was living in Monroe, Washington at the time and attending the General Conference Mennonite church there. My young husband and I became good friends with the pastor, and one evening after dinner at his home we went into the library where I noticed a multi-volume set of books titled Mennonite Encyclopedia.* — A Mennonite encyclopedia! I’d no idea there was such a thing! I looked through it, read some of the entries, then looked under the name “Willems.” Yes, there it was. My family name was in the encyclopedia! I wanted to know more, and Reverend Kopper, seeing my interest, offered to loan me a one-volume book on Mennonite history that was also in his library. That book was The Story of the Mennonites by C. Henry Smith[i]. Reading it, I was surprised to learn that the Mennonite people reached all the way back to the earliest years of the Protestant Reformation in Europe—to Switzerland in the early 1520’s and the reformers called “Anabaptists” because of their rejection of infant baptism. Smith describes these people as the “radical wing” of the Reformation, radical because they insisted upon things we now take for granted as obviously right—individual freedom of conscience and the separation of church and state. This radical position came from their reading of the Bible. What they saw in the New Testament was not a state church, but a church that was voluntary, a “free, independent religious organization” composed of adults baptized after a deliberate decision to take on the difficult demands of Christian discipleship, a radical discipleship that took literally the command to love one’s enemies, to refuse to return evil for evil. That command prevented them from “taking up the sword.” They refused to take up the sword in the service of the state; they even refused to defend their own lives, or the lives of those they loved—beliefs that were swiftly put to the test. The first adult rebaptism took place in 1525. This adult rebaptism with its implicit rejection of the legitimacy of a state church was perceived as a threat to social and political order by Protestant as well as Catholic rulers, and they acted quickly to try to stamp out this dangerous movement. Anabaptist men and women were “broken on the rack, thrown into rivers and lakes, burned at the stake, beheaded and buried alive” by Catholic, Lutheran and Calvinist governing authorities. Fifteen hundred of these terrible deaths eventually found their way into The Bloody Theatre or Martyrs’ Mirror, the Mennonite martyrology compiled in 1660 by Thieleman J. van Braght. That number is now considered very conservative. Persecution effectively eliminated the Anabaptist movement in much of Europe. Those who survived lived as fugitives seeking refuge wherever they could find it—in relatively tolerant cities like Strasbourg and on the estates of nobles who wanted the skills and labor of these hard working, frugal people. Taking advantage of every toe-hold they could find, these people of radical faith managed to maintain an embattled presence in areas of Switzerland and the lands along the Rhine, in particular, Alsace, the Palatine and the Netherlands.

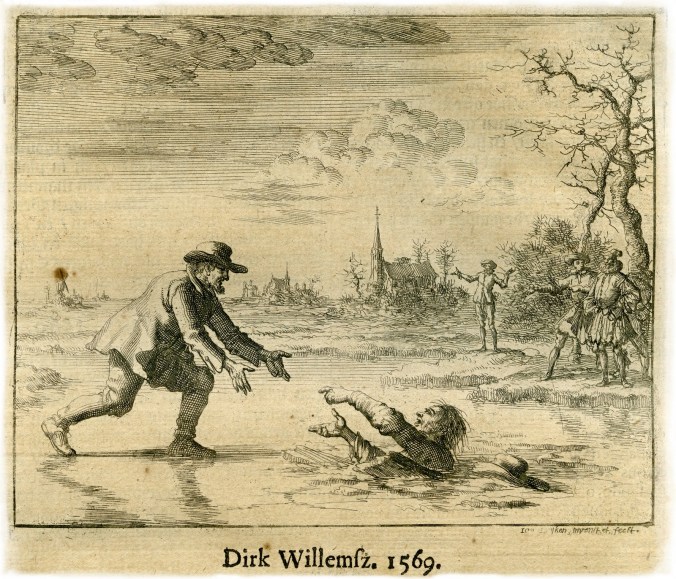

A page from the Martyrs’ Mirror. Dirk Willems is one of the most famous of the martyrs. He is here rescuing his pursuer, who returned Dirk to prison where he was later burned to death. To read more of his story click on the following link: https://www.goshen.edu/mqr/Dirk_Willems.html

Not all of those who rejected infant baptism and a state church, however, refused to take up the sword in self-defense. The movement was diffuse and divided. With its early leaders quickly identified and executed, the movement was floundering, easy prey to men with apocalyptic visions and calls to revolution. In the midst of the chaos and despair, the shattered movement found a new leader who rejected violence, Menno Simons, a Dutch priest who left the Catholic Church in 1536. This effective debater, diligent traveler and voluminous writer, was soon identified with peaceful Anabaptists in Switzerland and the Rhineland as well as in the Netherlands, the name ‘Mennonite’ used to distinguish non-violent from violent Anabaptists. Intense persecution did keep Anabaptisim from becoming a mass movement. However, it also created a new people, a people with a distinct identify, a people who felt compelled to help each other survive. My Willems family descends from Mennonites from the Netherlands who found refuge in the Vistula River delta in what is now Poland. Artisans and farmers, these Dutch, Frisian and Flemish Mennonites knew how to turn swampland into productive farms, skills that made them valuable to people who ruled the delta. Granted protection because of their economic worth, they were allowed to maintain their distinctive beliefs, but were forbidden to take converts or marry into the local population. Here in the delta, after initial severe hardship in which it is estimated that up to 80% of the first generation of settlers died of “swamp fever,” they prospered and increased, developing their own distinctive Plautdietsch dialect, carrying into the twentieth century the same family names they brought from the Netherlands. For two hundred years, Dutch was the language of Vistula Mennonite literacy and worship. Dutch was gradually replaced by German in the eighteenth century when the people of the Vistula delta came under Prussian rule. Plautdietsch, however, remained the language of home and daily life. Prosperity and increased population also brought problems. The presence of large settlements of people who were exempt from military service, yet remained separate and different from those around them, bred resentment among the local population. Pressure was put on governing authorities, and laws were enacted forbidding Mennonites to acquire more land. Families could no longer provide farms for all their children, and a landless class developed within the Mennonite community. Then in 1786, an agent of Catherine the Great of Russia, seeking German settlers for newly conquered land just north of the Black Sea, approached the Mennonites with enticing offers of free land, exemption from military service, the privilege of self-regulation and financial help in the resettlement process. In the following half-century about half the Vistula Mennonite population migrated to the steppes of what is now Ukraine. Here again, in this new land, which the Russian authorities referred to as “New Russia,” they again prospered and increased after initial severe hardship, building a veritable Mennonite “kingdom” of people originating in Holland, with Dutch names, who had become part of German language culture at the end of the 200-year sojourn in the Vistula delta. Plautdietsch, however, remained the beloved language of home and daily life. The Mennonites’ charter of privileges not only granted them religious tolerance and exemption from military service, it also allowed them to be a separate, largely self-governing people with their own distinctive culture. Then in the 1850s the reigning czar, Alexander II, began a program of “Russification.” Pressure was put on Mennonites and other minority groups to assimilate with the Russian population. New laws threatened both their control of colony schools and the exemption of their sons form military service. The Mennonites of south Russia began to look for a new land. They found it in the prairies of North America. A new migration began. In the period between 1873 and 1884, 18,000 Mennonites, about half the population of the Russian colonies, left for the virgin prairies of the United States and Canada, taking their Turkey Red wheat and knowledge of dry land farming with them. There they again, after initial hardship, prospered and increased. Over half the population, however, stayed in Russia. The czarist government, alarmed by the mass exodus of valuable farmers decided to allow the Mennonites to substitute forestry service and hospital work for active military service. Although, the government insisted that Russian was to be the language of instruction in Mennonite schools, for the most part the Mennonites were allowed to continue governing the internal affairs of their colonies. The colonies prospered. Secondary schools and hospitals were established. Mennonite entrepreneurs built large wheat mills and farm implement factories. That veritable Golden Age of Mennonite culture ended abruptly, drastically in 1914 when Russia entered WWI. War with Germany was followed by civil war that brought anarchy and violence, disease and famine. In the Ukraine, the Red and White armies fought back and forth across Mennonite land. Soldiers confiscated food and livestock. Outlaws roamed the countryside attacking farms and villages, raping, torturing, maiming, killing. Resented for their wealth, suspect because of their German language and separatist culture, Mennonites became special targets, easy targets in the prevailing lawlessness, a situation that intensified with the victory of the Bolsheviks. In the summer of 1920, Mennonites in North America and the Netherlands concerned about the situation in Russia sent a commission to investigate. What they found was massive hunger and a land devastated by disease. Drought had struck the war-ravaged lands, and Russia was in the grip of massive famine, one in which millions of Russians died of starvation before it ended in 1924. Mennonites around the world organized to get food into the Ukraine, organized soup kitchens, distributed food and clothing, shipped in tractors to replace horses slaughtered for food, provided seed for replanting once the drought ended. The end of the famine eased the Mennonites’ plight. They were no longer starving, but it did not end their troubles. Seen as “kulaks” by the Soviets, their farms were confiscated, the churches and schools were seized, the preachers and teachers arrested. Mennonite life in Russia was doomed. All who could escaped—escaped with the help of Mennonites all over the world. North American and Dutch Mennonites negotiated with the Soviets to allow people to leave Russia. They negotiated with government leaders in North and South America to accept the refugees. Churches raised money to pay for trains and ships to carry the desperate people thousands of miles to the places that were to become their new homes. Canada accepted 21,000 refugees, Paraguay 3,000. The majority of Mennonites in Russia, however, were not able to escape before the Soviets clamped down and refused any further emigration. The Mennonites who remained in Russia effectively disappeared behind the Soviet wall until the end of WWII when about 35,000 Mennonites followed the German army out of the Ukraine. Most of them did not make it to safety. Many died along the way. Others were captured and sent back. Approximately 12,000 did make it to Germany and the refugee camps set up by Dutch and North American Mennonite. Half of the refugees were resettled in the Chaco of Paraguay and Uruguay, the other half in Canada. Helena Zimmermann, my Grandma Willems, was born in 1893. If her parents had not decided to emigrate to North America in 1903, she would have been 21 when Russia entered WWI in 1914. She would have experienced the famine and terror that descended on the Mennonite colonies. I and all my Willems aunts, uncles and cousins, sisters and children exist because Grandma’s parents made that fateful decision and acted on it.

*Note: The Mennonite Encyclopedia is now online in searchable format at http://gameo.org/index.php?title=Welcome_to_GAMEO

[i] C. Henry Smith. The Story of the Mennonites, 4th ed., revised and enlarged by Cornelius Krahn. Newton, KS: Mennonite Publication Office, 1957 (original copyright 1941). Direct quotes from pages 45, 13, 163. ©Loretta Willems, April 1, 2015

Loretta

This was your most interesting and valuable post yet!

Thank you!

Ray

Sent from my iPad

LikeLike

Thanks, Ray. I’m glad you liked it.

LikeLike

Thanks, Loretta — this was quite enlightening! — Loretta Carmickle

LikeLike

Hi Loretta, it’s nice to get your comment, and nice, too, to know you’re following my book.

LikeLike

Loretta – the many challenges over so many years and different countries is really an amazing story. It’s great you’re piecing this together. David

LikeLike

Hello David. Yes, that such a small group of people should remain historically visible over such a long period of time while moving from country to country and halfway round the world still awes me.

LikeLike

Thank you, Loretta. This chapter was a fascinating read.

LikeLike

Hi Ginger. I’m glad you enjoyed the chapter. It’s nice to know you read it.

LikeLike