Note: To read earlier chapters, click on the desired title in the “Chapters” section of the sidebar on the right or at the bottom of the page.

“On February 6, 1909, [Jacob C. Willems] was united in holy matrimony to Lena Zimmerman at Rosthern, Saskatchewan by the Rev. Brown. As a young couple they settled in Brotherfield, and lived there until 1919 when they moved to the United States and resided in the Dinuba-Reedley area.” Obituary for Jacob C. Willems (1964)

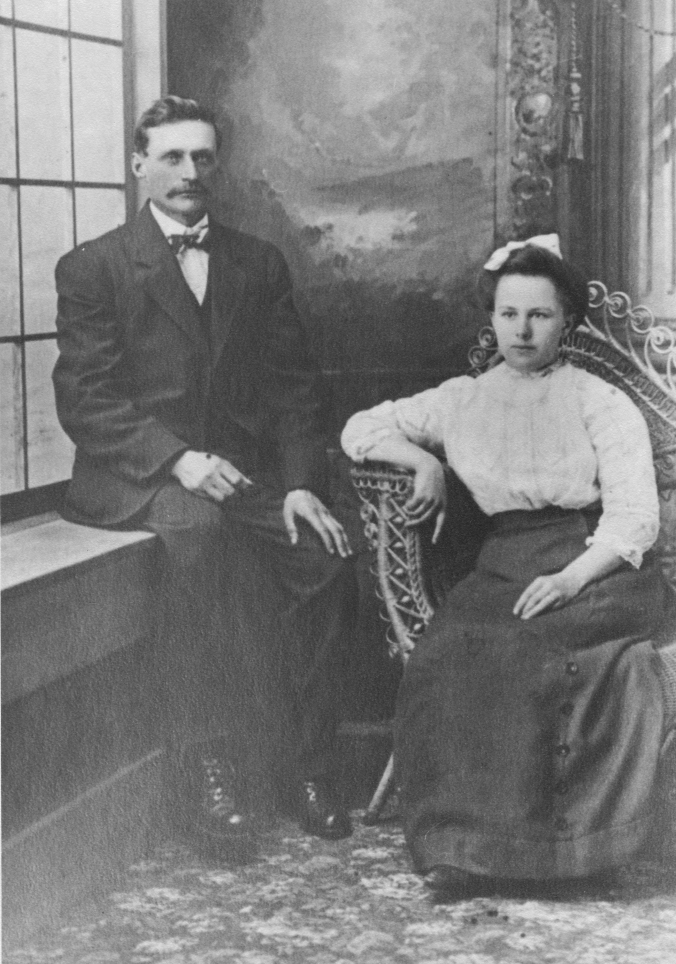

A large oval-framed copy of my grandparents’ wedding portrait hung directly opposite the door from the kitchen to the dining room of their house on Academy Way. I saw it every time I walked from the kitchen to the front of the house, and when the house was quiet and empty except for me and Grandma, I would stand and look at the young couple in the photo, fascinated by this view of my young grandparents. This was a photo taken in a different time than the one in which I lived, picture taken in the time of the Old West, a time of horses and buggies when women wore long dresses and men had handle-bar mustaches. Grandpa didn’t wear guns or a cowboy hat, but he looked like the Western gunmen I had seen in old photographs. His eyes looked steely, his expression stern. Looking at my young grandma in her Gibson Girl skirt and white lace blouse, I could see where my aunts got their love of clothes and sense of style.

Grandma looks as pretty to me now as she did back when I was a girl. She has lovely skin, regular features, beautiful, long-fingered hands and graceful arms. She looks sweet, innocent and tender—and very, very young. Grandpa, though, now that I look at him more carefully, no longer looks steely and stern. Even though his mustache turns down at the ends, he is not actually frowning; his mouth is not a hard line. He looks directly at the camera, but his eyes don’t seem to be challenging the viewer. He seems to be simply waiting, his face in repose.

What strikes me now is how separate they are. They do not look at each other; they do not touch. They may be married, but they look to be living in separate mental worlds. What also strikes me is the difference in their ages. Grandma is just a girl, a very young girl; Grandpa is a fully grown man. February 6, 1909, the day the wedding took place was the day Grandma turned sixteen. Her groom, my grandfather, was twenty-five years old. I seem always to have known that Grandpa was about ten years older than my grandmother, but it was simply a given. I gave it no thought. It is only now as a much older adult that the fact of that age difference looms large, feels like a critically important fact in understanding my grandparents’ marriage as well as their individual lives.

I am still fascinated by this photo of my grandparents. I would love to be able to enter their thoughts, know what they were feeling. I would like to observe them as lived their daily lives, attended church and visited family and friends. A few clues to that life remain—a story my grandmother told late in her life; a few snippets of my dad’s memories from just before his family moved to California; several wonderful old photos, an audio tape my father made at a 1980 Willems Family Reunion held near Waldheim; some online research, both my own and that of other descendants of Gerhard Willems. The picture that has grown is still far from complete, but what is there to be seen offers a tantalizing glimpse of my grandparents, their marriage and their life in Canada. I begin with the place where my grandparents met and spent the first ten years of their marriage, the Brotherfield area just west of the little town of Waldheim.

Waldheim

“The origins of the community date to the early 1890s with the settlement of large numbers of Mennonites in the area, a presence which remains strong in Waldheim to this day. The name Waldheim means ‘forest home’ in German, and was chosen as the district was well treed. The Waldheim post office was established in 1900, and with the arrival of the Canadian Northern Railway and the construction of the station in 1909 Waldheim became a railway center for the developing agricultural community in the rich farmlands of the surrounding area.” Encyclopedia of Saskatchewan (online)

The website for the town of Waldheim has a photo gallery that shows a town with tree lined streets and homes sheltered by healthy, mature evergreens. From what I see it looks like a pretty town, one that is not starved for water, not trying to survive under environmentally marginal conditions. I can see why they named the town Waldheim, ‘forest home.’ Trees can thrive here in Saskatchewan’s Parkland. The town did not look like this, of course, when the Willems family first arrived. It was just a speck on the prairie about seven miles due east of the quarter section of land on which my grandfather Jacob and his family settled when they arrived from Minnesota in the spring of 1900. Below is a photo of that land taken by Dennis Zimmerman, who took the photos of the pulpit featured in the previous chapter.

This is the land my great-grandparents, Cornelius & Elisabeth (Boldt) Willems, homesteaded in 1900. The Rose River School was built on the SW corner acre. My grandfather Jacob Willems helped farm this land until he had his own homestead. My grandmother Lena moved onto this land when her father, H.H. Zimmermann married Elisabeth Willems 18 March 1906.

This is the land my great-grandparents, Cornelius & Elisabeth (Boldt) Willems, homesteaded in 1900. The Rose River School was built on the SW corner acre. My grandfather Jacob Willems helped farm this land until he had his own homestead. My grandmother Lena moved onto this land when her father, H.H. Zimmermann married Elisabeth Willems 18 March 1906.

Adjoining this homestead on its west border was one staked by Cornelius’ brother, Abraham S. Willems. Abraham (1858-1948) and his wife Sara (Flaming1859-1936), along with their seven sons and two daughters, made the move from Minnesota to Waldheim the summer of 1899. Norman Jantzen[i], one of Abraham and Sara’s grandsons, who grew up in Waldheim and still lives in the area, has written an unpublished family history that includes a vivid description of the migration to Saskatchewan and the land where his grandparents built their new home:

“They boarded the train August 1, 1899 with the family’s personal belongings, enough food for the trip, part of which was a large sack of roasted buns, two cows, five horses (large grays), chickens, ducks, two wagons, two buggies, one binder and plow. The trip took only one week. … Upon arriving, grandfather left Rosthern the next morning with his older boys and a load of lumber to begin erecting a house on his homestead on Sec. 21, about 8 miles west of Waldheim. …

“The shell of the house was finished by freeze up. Until then most of the family slept in Isaac Neufeld’s hay loft. The site developed into a prosperous attractive farm with large buildings, beautiful fruit garden and shelter belt. There were a lot of horses, cows and even sheep to attend… The lumber for the new barn was delivered by river boat to Petrofka and brought up from there….”  A. S. Willems House

A. S. Willems House

“It was a beautiful choice location as many visitors later commented. Lush hay fields, low green bushes and just a few miles from the North Saskatchewan River where Saskatoon berries, strawberries, chokecherries and high bush cranberries grew in abundance, which were promptly canned for winter storage. Fish also were easily caught in plenty (4-5) … .

“Windfall wood was easily hauled out of the woods, so there was an abundant supply, available for winter. “The home was also a place frequently visited by distant friends and relatives, who stayed for several weeks. Often a trip to the river for fresh fish was part of hosting the guests. … “Indians also stopped by to see the new settlers, to trade flour and horses on their way from one reserve to the other” (6).[ii]

This was the land that greeted my grandfather’s family when they arrived in the spring of 1900. They would have been welcomed by Abe and Sara; there would have been visiting back and forth as the two families helped each other build their houses and barns. Both families were big, and the age range of the children almost identical.

My grandfather Jacob had twelve cousins living on the adjoining farm, the oldest five of whom were boys near his age. And they would not have been the only boys his age living close by. Mennonite families were big. Grandpa must have been part of a large cohort of young MB males, many of whom were his cousins.

My grandmother Lena, on the other hand, had no cousins, no aunts and uncles in Waldheim or any place else in North America. She was not a farm girl, but when her father Heinrich Zimmermann married the widowed Elisabeth Willems, she suddenly found herself living on a farm in a huge pre-established family. The five Zimmermann children now lived in a house with nine step-siblings. Four of those step-brothers and sisters were their own age, but the other five were older, some much older. The Zimmermann children must have felt disoriented and intimidated, over-whelmed and out-numbered.

The Willems brothers and sisters may well have resented their new step-siblings, complete strangers who had invaded their already full house. The older boys, however, also likely took notice of thirteen-year old Lena and her almost-twelve year old sister Anna, young females at the threshold of adolescence who were not the Willems boys’ blood relatives, hence potential marriage partners. My grandfather Jacob and his older brother Cornelius likely welcomed their mother’s marriage. Cornelius was twenty-three, my grandfather Jacob twenty-two. Now that their mother had a new husband they were free to begin building their own lives, work their own homesteads.

Willems Family Reunion 1980[iii]

In the summer of 1980 my parents attended a Willems family reunion that was held at Bethany Bible Institute in Hepburn Saskatchewan, which is just a few miles southwest of the town of Waldheim. My father gave one of the sermons at the worship service held on the Sunday of that reunion weekend. He made a tape recording of the service which I found in his files after his death. Fortunately I have a good cassette player, and when I inserted the cassette and punched “play,” I suddenly heard a full voiced choir singing—a large and very good choir. When the worship leader (Sam Willems) comes on, he asks the congregation, “Wasn’t that a great choir? A Willems choir! Have you ever heard one like that before?” That entire choir, as well as the pianist who accompanied them, belonged to the extended Willems family, the descendants of the twelve children born to Gerhard Willems (1820-1900) and Katharina Remple Willems who came to North America in 1875.

Following the opening words in which Sam Willems thanks the school for opening their facilities for the reunion, he says a few words about the ties between the school and the Willems family. Members of the family helped to establish the school, served on its board, taught there and attended as students. These opening words are followed by congregational singing—and that congregation sounds huge, the auditorium a large space full of people singing four part harmony. The singing is led by Arthur Willems. Elmer Willems, my father’s double cousin from Dinuba, reads the Bible text. After the scripture reading, Sam Willems introduces my father, who is to give the first sermon of the day. One of the things Sam mentions is that Dad had been born “west of Waldheim down by the river someplace. Some of you know where Earl Harder lives. Well, that’s the place.”[iv]

The Place by the River

“What struck me the most was, well, the beauty of the place. It was just an ideal spot. The place was on top of a kind of a bluff with a river flowing down below it.” Frank Willems

My father and his brother Frank saw the place by the river Sam Willems mentioned. Their uncle Herman Goosen, the widowed husband of their mother’s youngest sister, Marie, drove them to the place while they were at the Willems Reunion. Uncle Frank and my father both said it was a beautiful piece of land on a bluff overlooking a river. That river was the North Saskatchewan. The the land below the bluffs where their family once lived was where the Northern Cree had over-wintered before the region was opened for homesteading.

An old shed was on the property. Herman Goosen said that this shed was what remained of the house their family had lived in. Frank said that it had been cut in two. “The part that I saw was just 12” boards for walls and, I guess you’d call it board and batten, with little strips to cover the cracks. And I looked at that and thought, “How in the world could they keep warm with that kind of a building, especially with the kind of heating they had?”

Waldheim: Jacob C. Willems Homestead with the “house” Herman Goosen identified as the one where they lived with their children.

Homesteading

Canadian Homestead records show that on April 14, 1905, my grandfather, Jacob Willems, filed a claim on a quarter section of land seven miles straight west of the town of Waldheim.[v] Homestead law required that a dwelling be constructed in order to prove up a claim. This thin-walled shed my dad and uncle Frank saw may well have been the remnant of the “house” my grandmother moved into on her wedding day, the house where she would give birth to child after child. Eight of the fifteen children she would eventually bear were born in Saskatchewan.

Bearing child after child in a small house on the Canadian prairie, cooking and cleaning and keeping them clothed and safe while either pregnant or nursing is not something I can fully imagine. I could not have done it. I also married and had children when I was very young. I know how hard it was, how burdened down I felt—and I was not nearly as young as Grandma. Seventeen when I graduated high school and married, eighteen when my first child was born, I had only two children total. And I didn’t live in on the Canadian prairie in a house that must have been almost impossible to keep warm. It could not have been easy. My young grandmother must have felt chronically tired. She must have experienced at least some depression.

Living on that homestead was not just hard on Grandma. It was hard on Grandpa as well. Creating a fully productive farm out of raw prairie took enormous effort. It was hard, grueling work, and it was expensive, requiring a capital outlay of thousands of dollars to successfully prove up a claim. As Canadian prairie historian Gerald Friesen has noted, ’free’ homesteads in some respects were “costly beyond computation”:

“Whether by dint of hard work in northern logging operations, western mines, railway construction sites, or itinerant harvesting crews, whether by virtue of neighbourly assistance or family contributions, each homestead unit would require a capital outlay of several thousand dollars in the period of proving up (three to eight years, generally speaking).”

“The rate of attrition—the failure of the homesteader to ‘prove up’ and thus obtain a patent for his quarter-section—was extraordinary. Chester Martin long ago calculated that four in ten prairie homestead applications were never fulfilled. Though admittedly rough, his statistics indicated a rate of failure of . . . 57 per cent in Saskatchewan (1911-1931).”[vi]

Homesteading required capital. Abraham Willems, whose large house was pictured earlier, was able to build as soon as he arrived in Waldheim because he had money from the sale of his farm in Minnesota. Norm Janzen writes that his grandparents, Abe and Sara, arrived with “cash in hand, lumber and supplies, horses and cattle” (4). My great-grandparents, Cornelius and Elisabeth Willems, would also have had money from the sale of their Minnesota farm and may well have been able to build a house for their nine children soon after arriving in Saskatchewan. My grandfather Jacob, however, was just a young man, starting from scratch. He did not have the capital with which the previous generation of Mennonite settlers began their lives in Saskatchewan, and his house shows it. Homesteading without sufficient start-up capital would have been both physically and emotionally grueling.

King and Duke

“My dad had lovely horses in Canada. That’s where he had King and Duke and some other horses. When he would harrow, he would stand on the harrow—he had a board across it, and I would want to go along. He would plant the seed and then we would harrow it, and I’d stand up front leaning against him on that plank, and I thought it was so great, seeing them horses.” Jacob J. Willems[vii]

Life for my grandparents was not just grim hard work. They were not isolated out on a barren prairie like so many of those who staked homesteads on the North American prairie. They were part of a large family; they were surrounded by farms owned by other Mennonite Brethren families. Keith Kroeker’s homestead map* shows their parents Heinrich & Elisabeth’s farm was just a mile and half away, the MB church just three and a half miles—easy drives even in a horse-pulled wagon. My grandmother and grandfather’s younger sisters most likely came to stay and help my grandmother with her babies and little ones. Grandpa’s younger brothers likely came to help him with work on the land. My grandparents enjoyed their brothers, sisters and cousins, were close to them their whole life.

Mennonites shared work, came together for harvesting and hog butchering. And Sunday there was church, visiting in the church yard before and after the morning service, visiting neighbors and friends on Sunday afternoons. Sunday afternoon MB families either went visiting or were prepared for drop-in visits. Coffee with sugar cubes accompanied by zwieback, the delicious butter-rich buns Mennonite women baked each Saturday. The kids would scatter into the yard and out-buildings to play; the men would check out the livestock and crops; the women would share news of family members not present. Sunday was the high-light of the week, a time for laughter and singing and sharing memories and stories, the reward for the previous six days’ hard work.

Little remains of those stories. Mainly they are snippets of things overheard while listening to my dad visit with his brothers and sisters. There is one exception, a story my grandmother told when I was present that captured my imagination and has been with me ever since.

The First Automobile in Waldheim

Sometime during the early spring of 1960, my father drove Grandma and Grandpa from Dinuba to Phoenix, Arizona for a visit. My young husband and I were living in a house just a few miles from my folks’ place. We were sitting around the table on our patio one evening when Grandma told the only story I remember ever hearing her tell. It was about when she and Grandpa had lived in Canada. I have no memory of what sparked it, but Grandma mentioned that they had once owned the first car in Saskatchewan. She said that “Dad” (Grandpa) got it when he went to collect a debt, a large debt, that a man owed him for some horses. The man didn’t have the money, and to pay off his debt he offered Grandpa an automobile he had recently acquired. Automobiles were something brand new in their area of Canada, and though Grandpa had absolutely no experience of them, he figured that the car was better than nothing. He decided to take the car in payment for the debt.

Automobiles in those days were complicated to start and drive, not the simple things they are now. The man started the car then showed Grandpa the basic things he needed to know in order to drive it. Grandpa managed to get the car all the way home, but when he pulled into the yard he realized he didn’t know how to stop the engine. The noisy arrival at the house brought everyone out into the yard to see what was happening. There was a huge commotion. Grandpa was upset because he couldn’t figure out how to stop the car, and the kids were all excited because they had never seen an automobile, had no idea what this noisy monster was.

Finally, Grandpa decided the only thing he could do was to go back to the man who gave him the car and ask how to stop the thing. Deciding to take the family with him, he told Grandma to get the kids and put them in the car. When the car started down the road the little kids started crying and hollering, terrified by this noisy monster.

Exasperated, Grandpa turned around in the seat and swatted at them, telling them to shut up. The car swerved off the high crowned road and went into the drainage ditch. The car was still upright and still running, and Grandpa managed to get back on the road and continue on to the former automobile owner’s place. When they got there, however, they had a very bad surprise. The car bottomed our when went into the ditch and broke an oil line. When Grandpa and the family got to their destination the engine was red hot, all the oil had been lost. The engine was completely ruined, the car now worthless.

Grandma laughed as she told the story, and Grandpa smiled—we all laughed. Visualizing that story was like looking at an old slap-stick movie. I’m sure the loss of that car was devastating at the time, not funny at all when it happened. But the events were now in the distant past. All that was left was a wonderful story.

Zimmermann-Willems Family Portrait (c. 1916-1917)

The photograph above is of the combined Zimmermann-Willems family. Heinrich and Elisabeth, the parents, are seated in the center. Seated next to them are their two oldest children and their spouses. Lena, my grandmother, sits next to her father. Jacob, my grandfather, sits on her other side. At the other end of the front row are Elisabeth’s oldest child, Cornelius, and his wife, Tina. Ranged behind are the rest of the Zimmerman and Willems children as well as the spouses of those who were married. Standing behind my grandmother is her sister Anna, who married Grandpa’s brother George. There were now three Willems/Zimmerman marriages. George stands behind Anna, the third male from the right in the back row.

The photograph above is of the combined Zimmermann-Willems family. Heinrich and Elisabeth, the parents, are seated in the center. Seated next to them are their two oldest children and their spouses. Lena, my grandmother, sits next to her father. Jacob, my grandfather, sits on her other side. At the other end of the front row are Elisabeth’s oldest child, Cornelius, and his wife, Tina. Ranged behind are the rest of the Zimmerman and Willems children as well as the spouses of those who were married. Standing behind my grandmother is her sister Anna, who married Grandpa’s brother George. There were now three Willems/Zimmerman marriages. George stands behind Anna, the third male from the right in the back row.

My grandmother Lena is twenty-three or twenty-four in this photo. Her sixth child was born in October of 1915, her seventh child June 26, 1917. She still looks young in spite of all that child-bearing and hard work of rearing children on a homestead. She still looks as sweet and tender as she does in her wedding portrait, but she does look rather worn down. She looks a bit sad, a bit depressed.

Grandpa is either thirty-three or thirty-four years old when this photo was taken. He wears a rumpled suit with a white shirt buttoned to the top, but no tie. He looks straight ahead. His eyes do look steely now, his face harder than in the wedding portrait. Still, he is a very handsome man.

Only three of the twenty people in that group have even the faintest hint of a smile. Smiling for the photographer wasn’t the fashion then, but the lack of smiles does make for a very somber effect.

Heinrich & Elisabeth Zimmerman with Grandchildren (c. 1916-1917)

I’m quite sure that the two little boys in the second row wearing dark suits are my dad and John. I recognize the pouty lip of the little boy in the exact middle.

I’m quite sure that the two little boys in the second row wearing dark suits are my dad and John. I recognize the pouty lip of the little boy in the exact middle.

The photo above was obviously taken on the same day as the large Zimmerman-Willems family portrait. My great-grandparents sit surrounded by grandchildren. Six or seven of those fifteen children belonged to Lena and Jacob, my grandparents—three of the boys in the front row (Nick, Stan, Henry), two of the toddlers behind them (Helen and my father), and one or two of the babies (John & possibly Mary).

In this photo, Elisabeth and Heinrich both smile.

Lena & Jacob with Children c. 1919

My grandparents, 1919. Their oldest son, Nick, is in the middle of the back row. The boys on each side of him would be Stan and Henry, but which is which I don’t know. Helen is the bigger girl, Mary the one on Grandpa’s lap. The two boys in front are John and my dad. My dad is on the end.

My grandparents, 1919. Their oldest son, Nick, is in the middle of the back row. The boys on each side of him would be Stan and Henry, but which is which I don’t know. Helen is the bigger girl, Mary the one on Grandpa’s lap. The two boys in front are John and my dad. My dad is on the end.

Judging by the ages of children, the photo above was taken some time in the summer or early fall of 1919. It looks like it might have been taken by a professional photographer. Everyone is nicely dressed. My grandfather Jacob and the boys all wear suits. The three older boys wear white shirts with ties. My dad and his brother John wear identical Buster Brown suits—jackets with sewn in belts and round collars buttoned to the neck, knee pants with dark high socks. My grandmother Lena wears a slim black shirt with a white striped blouse. She sits with what looks like a baby blanket on her lap, her left arm holding a blur that is probably the small infant Frank, who was born 30 March 1919.

Grandma is slender, obviously not pregnant. Her hair is fluffed up and away from her face, no longer flat to her head and pulled straight back as in the Zimmermann-Willems family portrait. And she smiles, the only one in the photo to do so. Altogether, she looks more stylish, more confident than in the photo of the joint Zimmerman-Willems family. She looks happy.

Grandpa, however, has aged drastically in the three years since the large group portrait was taken. His face is weathered. He now wears glasses. He is only in his mid-thirties, turning thirty-six the summer of 1919, but he looks much older than that.

That summer of 1919 was the last the family spent in Canada. In the fall they sold out and boarded the train, headed for California.

Going to California

“Helen was the fourth child, and I was the fifth. My name is Jacob. Helen and I were great pals. We sat in the same rocking chair and daydreamed about going to California. We had a calendar that had an apple tree picture on it, and a little boy with a wheelbarrow picking up the apples under the tree. This was a conversation piece that never ended. It was so real. We thought we could just pick them and eat them. Of course we could wait till we got to California to eat them. There were better apples there.

“When we moved to California we had to have an auction sale in Canada. We were all excited about living in California. We held our breath [to see] if the auction sale would bring enough money to bring us to California. When all had been sold on the farm, –[including] a new colt that I felt was mine–, many tears were shed. But Mama had to get out of the cold climate. She had rheumatism so bad we thought she would die.”

My father said that the reason his parents moved to California was because his mother had “rheumatism so bad we thought she would die.” I think there was more to it than that. There was the lure of California itself for people living and farming in the extreme cold of Saskatchewan winters, a land of sunshine and mild winters, a land where a little boy and girl could pick fruit right off the tree.

*Re Keith Kroeker’s Homestead Map, see Ch. 10

Copyright: Loretta Willems, Oct. 1 ,2015

~ ~ ~ ~ ~

[i] Norman W. Janzen. A Good Land: The History of the Abraham S. Willems Family in Canada 1899-1999 (unpublished). Norm contacted me after discovering my family history blogsite and offered to share information about the Willems family I didn’t have.

[ii]Based on an account written by Lawrence Willems found in the Waldheim History, 1981.

[iii] It was this reunion that generated the genealogical information on which all my genealogical research was based.

[iv] Sam Willems also mentioned that Dad’s Grandfather Zimmerman made the pulpit for the Waldheim church and spoke about the connection of the Zimmermans to the Willems family. The rest of the tape was taken up by Dad’s sermon.

[v] The South West quarter of section Twenty, of “township Forty-two, range six, West of the Third Meridian, in the Provisional District of Saskatchewan in the North West Territories, in our Dominion of Canada.”

[vi] Gerald Friesen, The Canadian Prairies: A History (University of Toronto Press, 1987), 310, 309.

[vii] Taped interview, June 4, 1994.

The pictures are wonderful, and I thought this was one of the best chapters, so far!

LikeLike

I’m glad you liked it. This went through many drafts to make it more than a disjointed collection of disparate elements, and I wasn’t at all sure I’d succeeded.

LikeLike